Creativity in exile

GA: This is a large segment of an interview I gave to Melissa Hekkers (in-cyprus.com) last week in Nicosia. I had a fascinating discussion with Melissa and I am happy with the way in which she delivered my thoughts.

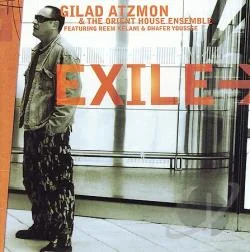

Melissa Hekkers interviews Gilad Atzmon

Listen to the OHE and Dhafer Youssef playing La Cote Mediterranee

The Wandering Who?

We meet in the old town of Nicosia, in the basement of the Windcraft Centre. I’m perplexed as to what we’re going to talk about; there are so many sides to Atzmon’s story I’d like to address; I’d like to know what he thinks about the world we live in today, from an expat Israeli’s point of view.

I want to ask him about migration and refugees. I want to know what it feels like looking back on his homeland. I’m curious about what brings him to the island so often. I want to pick his brain about sharing his time between music and academia.

Aware of his profound sense of humour, counting the number of sheftalia he’s eaten since he arrived on the island breaks the ice as he reveals the essence behind his attraction to the island.

“Cyprus is basically as close as I can get to my homeland, I cannot go back home – to go back is easy, whether they let me leave is another question – which is understandable: I really oppose everything they do, not as Israel, I oppose all forms of Jewish politics, including the Jewish anti-Israelis and the reason that I oppose all forms of Jewish politics is because it is racially-oriented,” Atzmon declares as we get comfortable.

Carrying Gilad’s book “The Wandering Who” on Jewish identity politics in my bag, I’m dubious about getting too deep into politics. I interrupt him. “Who do you speak to when you write books?” I ask.

“It’s quite an interesting question,” he retaliates as he throws his saxophone neckstrap to the side.

“Rather than talking to Jews, which I may as well do, I talk about Jews and it’s very important that I refine that: I don’t talk about Jews, the people, I talk about their culture.

“One would have expected that considering their history that is basically a continuous holocaust with a few tea breaks, they would be the first people to locate themselves at the forefront of anti-racism, anti-oppression and it’s a quite embarrassing fact that just the three years after the liberation of Auschwitz, they wiped out Palestine, they ethnically cleansed 75% of the population, they wiped out the entire civilisation.”

I remind myself later that evening that he was playing with some of the leading local jazz musicians, Ermis Michail, Irinaeos Koullouras, Stelios Xydias to name a few, without dismissing his collaborations with Ian Dury, Robbie Williams, Sinead O’Connor, Paul McCartney, Pink Floyd…

And although I’m relieved when he turns the conversation towards a local front, I also accept that steering away from talking about what he knows best is not feasible.

“Two days ago I went to meet my best friend on the island; he’s now living in a house near Polis that was disserted by a Turkish family. He took it when it was a complete wreck and he rebuilt it, but you are in the village and you see the Turkish village is still there.”

“Palestine should have been the same, the houses should have still been there. Israel was very quick to wipe it out.”

I refer to the strong identity Palestinians hold, regardless of their fate.

“It’s very interesting because the Jews, as we know them, never had a home, and this is something that is quite crucial. Judaism was born in Babylon when Jews were in exile and they were starting to assimilate, they were a very friendly, very tolerant society.”

“Eventually, some Jews became horrified at the possibility that Jews won’t be Jews again, so, in a way, the situation in Babylon 2,500 years ago was similar to the birth of Zionism in Europe in the 19th century.”

“Then they invented Judaism as we know it today and it is an exilic culture; this is very different from all other cultures that you can think of. It’s a culture that is based on the fantasy of return, this is why Jews are set to live in a negation with their surrounding reality; this is why they isolate themselves.”

I grasp at the notion of the fantasy of returning home and try to revert our conversation back to a local front.

“That friend of mine (in Polis), is a refugee, he’s like a Palestinian, I speak to a lot of refugees (in Cyprus). It’s very interesting because the situation is very similar…

“A lot of refugees want to solve the issue, to bring peace, to settle it, they have a lot of issues, it’s not simple, there are a lot of empires involved, but I don’t see any of that within the Israeli society. Israel still hasn’t acknowledged the fact that the Jewish state wiped out an entire civilisation, this is quite unusual.”

Breaking away

But how easy is it for one to break away from their homeland, without return?

“To start with, I got a lot of things from Israel, I grew up there, I got a very good education, I became a musician, I think freely, unlike most western people now, this is something that I got in Israel…

“I didn’t have any problem to break away from it; I don’t even miss the place that much. In the early years when I missed it, I realised that what I miss is the country, and the country is Palestine, I was missing the sun, and the smell of the spring and hummus!”

Now living in Killburn, London, Atzmon has made Britain his home.

“I never thought that I would go to England, I never liked England as a tourist… but when I moved there, I felt at home immediately…”

“I cannot think of people being more tolerant and welcoming than the English people. I had really incredible years in England, an incredible career, within two three years I joined the Blockheads, Robert Wyatt and I continue to play with a lot of great British musicians.”

He had a choice between London, Chicago and Berlin.

“Berlin wasn’t an option because my wife’s family were kind of holocaust survivors and her mother would find it hard to cope… had I moved to America I would have been an American by now…not that England is a vivid intellectual environment.

“Being in Europe, being here (Cyprus) every three months, touring, being in France, being in Germany, being part of this very lively society that is part of the EU, but still multi-ethnic, multi-ideological, diverse is a great opportunity.”

Upholding our identity

So who is Atzmon and how does he define his identity?

“Identity is a very ugly business. It’s in practice a form of identification, Identification is set to remove you from yourself.”

“I’m disgusted with identity politics, you will never hear me speaking 'as a saxophonist', 'as an ex Jew'."

“All this ‘as a’ is a wrong approach, it’s anti-human, it is there to split us. I don’t have to speak as a saxophonist, I am a saxophonist, I’m here in Cyprus, I played three or four gigs, I just gave a master class, if I were not a saxophonist of a reasonable calibre, I wouldn’t do it."

“I’m making a living being me, I’m making a living doing Gilad. I write books, I write papers, I play fast and loud, and I’m often very funny, this is me, there is no mediator, there is no ‘as a’…”

What ties us, however, is the land we live on.

“Once you settle on land you become part of it; soil, being part of the land, being part of the culture and loving the sky is the real meaning of patrio-tism, this is the real meaning of nationalism and I think this is a wonderful thing.”

“It’s something that I received in Israel, it was fake nationalism, but I can see how strong it is and I think that we are moving towards being natio-nal socialists… I’m not saying that we’re becoming big dictators and we hate foreigners and so on, but if global capitalism is cancer, the answer to global capitalism is national socialism."

We live in a frightening world, I exhale.

“I think we have come to a point where we have reached a plateau.”

“The credit crunch in 2008 happened because were not productive anymore, so we started to buy credit and kept buying and buying, we’re living in a consumerism society, politicians’ role is sustaining consumption rather than looking after people, and eventually they realised that we were buying with money what we didn’t have…"

“Now the bubble is growing again and we have come to a point where in order to fuel the system, we have to push it down to zero.

“Cyprus, against all odds, is in a reasonable shape because you’re a small country… Even if everything becomes very dark out there and the EU collapses, you’ll still have sheftalia here, you have good tomatoes, you have lemons, you have oranges, maybe you won’t have a Mazda, but even if you have to walk, you have a small country.”